| Opening Concert | ||||||||||

Don Juan, Op. 20, Tone Poem after Nikolaus Lenau Richard Strauss came from an extremely conservative family. His father, Franz Joseph, the principal horn player in the Munich Court Orchestra, considered Brahms a radical and Wagner’s music beyond the pale, forbidding his son to listen to it. Richard assimilated the music of the early and middle nineteenth century in his early works, composing as a committed classicist. But he soon discovered that the musical language taught by his father was too confining for his own fertile mind. Strauss quickly found his voice through his own unique development of the tone poem, or symphonic poem, a purely instrumental rendition of a text, usually poetic or narrative in nature. The term “symphonic poem” had been coined by Liszt in 1854 for compositions accompanied by a program that the audience was supposed to read before listening to the music. Although nineteenth-century Romantics did not all use Liszt’s term, the genre had become a standard medium for Berlioz, Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky, reaching its apex with Strauss. Strauss’s musical rendering of specific texts is far more detailed than Liszt’s, although it is often difficult to follow without a “road map.” The anecdotes about Strauss' attempts at narrative music are many: “I want to be able to describe a teaspoon musically,” he is said to have commented. In the ten years between 1888 and 1898 he produced a string of tone poems, beginning with Aus Italien and Macbeth. Don Juan, completed in 1889, was the first to be publicly performed, catapulting him to international recognition. Don Juan represents Strauss’s liberation from the confines of his father’s restrictive world. He completed the score in Bayreuth where he was a coach at the Festspielhaus, the venue Wagner had built to showcase his music dramas. At the time, the 24-year-old Strauss was involved in a scandalous love affair with a married woman. He expressed his youthful exuberance and desire with three extracts from Don Juan, an incomplete verse play by Nikolaus Lenau (1802-1850), which he copied as a preface in the score. Lenau’s play is just one of the incarnations of the Don Juan legend, which first appeared on the literary scene in the seventeenth-century Spanish play El burlador de Sevilla (The Trickster of Seville) by Tirso de Molina, and was immortalized musically in Mozart's opera Don Giovanni. Lenau's version follows Don Juan through five debauched conquests that leave a wake of misery and death. In response to his brother’s attempt to dissuade him from his dissolute lifestyle, Don Juan expounds on his desire to experience all the diverse and novel joys of sexual gratification, hoping to die of a kiss from the ideal woman. His paramour/victims are: Maria, who follows Don Juan to escape from a forced marriage and is abandoned; Clara, who actually rejects him before he can reject her; Isabella, whom Don Juan seduces, disguised as her fiancé; Anna, who never actually appears but whom Don Juan apostrophizes from afar; and finally, an unnamed woman who dies of a broken heart. Don Juan receives the news of her death at a masked ball. Unlike Tirso's Don Juan and Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Lenau’s hero is not felled by a stone dinner guest meting out divine retribution. Rather, he intentionally lowers his guard during a duel with the son of one of his victims, whose father had become collateral damage during one of the Don’s exploits, because victory, and even life itself, has lost its appeal. All this, Strauss condenses and transforms into a single symphonic movement in sonata allegro form. While presenting a narrative in music, Strauss' tone poems also conform to the current conventions of musical form. In the case of Don Juan, Strauss adapted the narrative to a modified sonata allegro structure. The principal theme, incorporating an orchestral fanfare and an upward-swooping melody, is a composite musical idea expressing the wild abandon and sexual striving of his hero.  There follow three subsidiary themes representing the Don’s conquests. Although it is difficult to identify any of the specific paramours of the source play, Strauss creates a different “character” for each of the secondary themes that reflect their diverse personalities and qualities of love: one theme introduced by a soaring introduction on a solo violin; There follow three subsidiary themes representing the Don’s conquests. Although it is difficult to identify any of the specific paramours of the source play, Strauss creates a different “character” for each of the secondary themes that reflect their diverse personalities and qualities of love: one theme introduced by a soaring introduction on a solo violin;  & &  a second accompanied by a gasping flute theme a second accompanied by a gasping flute theme  and a sultry Spanish oboe melody; and a sultry Spanish oboe melody;  all develop alongside the restless motives of the Don. all develop alongside the restless motives of the Don.The second half of the tone poem – the development in formalistic terms – begins with the so-called “Carnival Scene” that corresponds to Lenau’s masked ball. Strauss breaks free of the sonata form tradition, however, by redefining the Don's personality with a new heroic theme, which has become the best known signature tune of the piece.  it also signals a turning point, the beginning of his downward slide, including the haunting of his conscience by his former lovers, whose themes recur to haunt him. it also signals a turning point, the beginning of his downward slide, including the haunting of his conscience by his former lovers, whose themes recur to haunt him.  Strauss alludes to further unspecified adventures in the increasingly manic development of the Don's themes. Eventually he wanders despondently through a churchyard where he comes upon the statue of a nobleman whom he has killed, and in a final act of bravado invites him to supper. The recurrence of the Don's original theme is Strauss' abbreviated take on a formal recapitulation – forgotten are all his earlier amours. Instead of the stone guest, the nobleman’s son arrives, seeking revenge. Don Juan puts up a valiant fight, during which all his themes are further developed and contrapuntally combined in a manner the composer certainly learned from Wagner. Suddenly the music halts and a minor chord precedes a blast on the trumpets  as Don Juan surrenders to his adversary and his despair – the opposite of Don Giovanni’s fiery defiance. Pianissimo timpani and pizzicato basses conclude the piece. as Don Juan surrenders to his adversary and his despair – the opposite of Don Giovanni’s fiery defiance. Pianissimo timpani and pizzicato basses conclude the piece. | ||||||||||

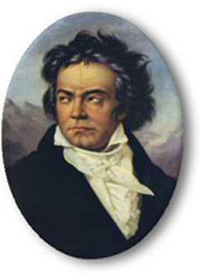

Romance No. 1 in G major, Op. 40 At the turn of the nineteenth century the Romance was a popular musical form, slow in tempo and simple in structure. It was a natural musical form for Ludwig van Beethoven, who considered himself a “Tone Poet.” Little is known about the circumstances of the composition of the Romance in G major except that it was probably composed in late 1801 or early 1802 and published in December 1803. One unusual feature of this piece for orchestra and soloist is that the solo violin begins it. The violin continues to dominate throughout, with the orchestra mostly just echoing the solo line. The Romance is a simple rondo with a refrain  and two episodes of new, but related, melodies. and two episodes of new, but related, melodies.   | ||||||||||

| Ludwig van Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major, Op. 50 The circumstances of the composition of the Romance in F major are obscure. It was probably first performed in November 1798 by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, whose Schuppanzigh Quartet – probably the first professional string quartet – was later to premiere many of Beethoven’s string quartets. It was published in 1805, but the autograph score has the same physical characteristics as the score of the Piano Concerto No. 2, which was also finalized around 1798. But according to Barry Cooper in his book Beethoven (Oxford University Press, 2000), both works may have been written much earlier: the Piano Concerto is a probable revision of a Bonn work from 1791, before Beethoven’s move to Vienna, and the Romance could be a reworking of the missing slow movement of the Violin Concerto in C major (WoO 5) of which only part of the first movement has survived. At the time, the title “Romanza” was frequently used for slow movements of violin concertos. The Romance is a song without words, consisting of a refrain  that alternates with increasingly passionate “verses.” that alternates with increasingly passionate “verses.”  & &  Beethoven concludes the Romance with an embellished version of the refrain, all in all creating a lovely musical arch. Beethoven concludes the Romance with an embellished version of the refrain, all in all creating a lovely musical arch. | ||||||||||

Selections from Romeo and Juliet, Op 64 While still a student in the St. Petersburg Conservatory before the Russian Revolution of 1917, Sergey Prokofiev was already known as Russian music’s enfant terrible. His First Piano Concerto in particular, with its spiky dissonances and unromantic tone, clashed with the taste of the prevailing musical establishment and his teachers at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, especially its head, the conservative Alexander Glazunov. Apolitical and appalled by the mayhem created by the Revolution, Prokofiev left his native country in 1918, settling first in the United States and then in Paris. But he never felt comfortable on foreign soil. By 1933, homesickness was consuming him: “The air of foreign lands does not inspire me because I am Russian and there is nothing more harmful to me than to live in exile,” he told a reporter in Paris. He was spending more and more time in Russia, although his family was still living in France. In 1936 he returned permanently to Moscow, aware that he would have to change his compositional style to satisfy Soviet cultural demands. He was never again able to travel abroad. The idea of composing a ballet based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a relatively “safe” lyrical subject, came to Prokofiev in the spring of 1935. A ballet on the same topic, written in 1925 by the English composer Constant Lambert for impresario Sergey Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, may have given him the idea. After returning to the Soviet Union, Prokofiev received a commission for the ballet from the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad; when Kirov backed out, the Moscow Bolshoy Theater took it over. Prokofiev tried to adhere as closely as possible to Shakespeare’s play, using both dance and mime to convey the story. When his innovative and complex score frightened the Bolshoy and the cast declared the music “undanceable,” Prokofiev revised the score. Their insistence, however, that the ballet have a happy ending turned out to be more than he could stomach. Romeo and Juliet was dead in the water. In the end, a hugely successful premiere took place in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in December 1938. Embarrassed, the Kirov took it on once again and after much wrangling, the ballet was finally premiered in Leningrad in January 1940. Galina Ulanova, the ballerina who danced Juliet, expressed the difficulties surrounding the production in a humorous parody of Shakespeare’s epilogue to the play: “There never was a story of more woeRomeo and Juliet is a long ballet with 52 numbers, but the rapid switches between dramatic and lyrical sections assure that the tension is maintained. One of the reasons for the ballet’s immediate acceptance was the fact that by the time of the premiere, the music was already well-known. In view of the production delays, and never one to let good music go to waste, Prokofiev arranged two orchestral suites from the ballet score, which premiered in 1936 and 1937. During the same period he also made a piano arrangement of ten excerpts and performed them in Moscow. He assembled the Third Suite from the ballet in 1946. It is common practice now for conductors to excerpt their own suites from the ballet. These suites, like Prokofiev’s own, do not necessarily adhere to the logical sequence of the story but are combined to be musically balanced. Today’s selections are: 1. The Montagues and Capulets combines parts of from Act I, where the Duke forbids the two families, on the pain of death, to continue their feud, | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2019 | ||||||||||