| STRAVINSKY FIREBIRD | ||||||||||

Overture to Colas Breugnon, Op. 24 In 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party took control of all of the arts, dividing them into unions according to discipline. The unions established the official aesthetic for the entire country; artists, writers and composers were obliged to submit their work for evaluation and criticism. All the arts were forced to adhere to an aesthetic of “social realism” that rejected the individualist, avant-garde movements in the rest of Europe in favor of a communal striving towards the ideal state. The result was that some composers, the most well known of whom was Sergey Prokofiev, ended up in geographical or cultural exile, their music frequently banned, their livelihood curtailed; some others, such as Dmitry Shostakovich, barely avoided Stalin’s gulags by maintaining a musical split personality; still others, such as Aram Khachaturian, while true believers in the Communist aesthetic, still fell in and out of favor for no recognizable reason. Dmitry Kabalevsky, one of the founders of the Union of Soviet Composers, stayed in line with the cultural constraints of the Soviet Commissars with a light, conservative and tuneful style. He contributed to many genres, including symphonies, operas, piano concertos and solo piano works. Like his colleague Shostakovich, he wrote numerous scores for propagandistic films and stage productions. His most valuable legacy, however, lies in the field of children’s music, including children’s opera, and a system of musical education. Several of his many instrumental pieces composed for young musicians gained worldwide popularity. Kabalevsky’s quasi-opera Colas Breugnon, based on a novel by the French Nobel Prize winning dramatist, novelist and philosopher Romain Rolland (1866-1944), premiered successfully in Leningrad in 1938. Its rollicking overture acquired a life of its own and, along with The Comedians, became Kabalevsky’s most popular composition. The story is about a sculptor during the time of the Black Death, who files suit against the Duke of Clamecy. The Duke is so angry that he orders the beheading of all Colas’s statues. Colas deflects the Duke’s anger by promising to sculpt a statue in full armor, but when the statue is finally unveiled, the Duke is portrayed sitting backwards on a donkey, and the townspeople’s laughter drives him back into his castle – a nice communist theme. The Overture features one of Kabalevsky’s favorite instruments, the xylophone. It opens a catchy tune with a syncopated, almost Latin American cadence.  A cymbal crash brings on a brassy circus melody pounded out by the xylophone. A cymbal crash brings on a brassy circus melody pounded out by the xylophone.  The plot thickens with a tense “movie theme” for the strings, The plot thickens with a tense “movie theme” for the strings,  but soon all turns out well with a return to the opening theme and a surprising ending. but soon all turns out well with a return to the opening theme and a surprising ending. | ||||||||||

Piano Concerto in D-flat major One of the most popular musicians in the former Soviet Union, Aram Khachaturian was originally trained as a biologist and only started to study music at 19. An Armenian – although born in Georgia – he had a knack for stirring rhythms and driving melodies, blending the orientalism of his native music with the lush Russian Romantic tradition. Beginning with his Piano Concerto in 1936 and including such later works as his Violin Concerto and the ballets Gayane and Spartakus, he created a series of compositions that became instantly popular around the world. In spite of Khachaturian’s popularity and leadership role in the Soviet Composer’s Union and his expressed opposition to modern experiments, he was not spared from interference by the Soviet bureaucracy. Together with Shostakovich, Prokofiev and a host of lesser composers, the Central Committee of the Communist Party chastised him for his “modernistic” transgressions. It was only after Stalin’s death in 1953 that he felt free again to compose in his own idiom. Khachaturian composed the Piano Concerto in 1936. Since he was not a gifted pianist, he sought the help and technical advice of Sergey Prokofiev, who had extensive experience in concerto writing. It was premiered in Leningrad in 1937 and became an instant favorite with the public and commissars alike. The fact that the Concerto highlights the modes and melodies of Georgia and Armenia, two of the Soviet republics, made its exoticism politically acceptable. The entire Concerto is rhapsodic in nature, its formal themes alternating with elaborate fantasies for piano in the traditional ambience of the steppe. It opens with fortissimo introductory chords by the whole orchestra, heralding the rhythmically compelling theme introduced by the soloist.  The contrasting second theme, introduced by the oboe The contrasting second theme, introduced by the oboe  leads into an almost improvisatory series of riffs, actually an internal cadenza, by the soloist. leads into an almost improvisatory series of riffs, actually an internal cadenza, by the soloist.  In this movement, Khachaturian employs the main theme almost as a refrain, periodically returning to it after the lengthy sinuous excursions of the piano. In this movement, Khachaturian employs the main theme almost as a refrain, periodically returning to it after the lengthy sinuous excursions of the piano. The slow movement is based on two melodies, the first of which, according to the composer, is derived from a melody once popular in his native Tbilisi. It is introduced by the bass clarinet,  an uncommon touch, after which the soloist immediately takes up a second theme. an uncommon touch, after which the soloist immediately takes up a second theme.  Throughout the movement, the composer also continually varies and embellishes these melodies in an improvisatory way. As in the opening movement, however, he periodically returns to the original unaltered version of the melody as a refrain or anchor, but with each reiteration intensifying the emotional clout. Throughout the movement, the composer also continually varies and embellishes these melodies in an improvisatory way. As in the opening movement, however, he periodically returns to the original unaltered version of the melody as a refrain or anchor, but with each reiteration intensifying the emotional clout.  At the conclusion of the movement, he returns to the bass clarinet theme and fades into silence. In this movement, Khachaturian made use of a curious instrument, originally used in jazz, the flexatone, which makes an eerie tremolo sound similar to that of the musical saw. One of those experimental instruments to fall by the wayside, the flexatone is now frequently replaced by a violin. At the conclusion of the movement, he returns to the bass clarinet theme and fades into silence. In this movement, Khachaturian made use of a curious instrument, originally used in jazz, the flexatone, which makes an eerie tremolo sound similar to that of the musical saw. One of those experimental instruments to fall by the wayside, the flexatone is now frequently replaced by a violin.The trumpet opens the exuberant and brilliant finale with its folksy dance rhythms.  Yet, in the first piano episode, one wonders where the composer heard the blue notes and American jazz syncopation so aptly applied. Yet, in the first piano episode, one wonders where the composer heard the blue notes and American jazz syncopation so aptly applied.  The momentum is interrupted by a long cadenza that extemporizes on Middle Eastern modes. The momentum is interrupted by a long cadenza that extemporizes on Middle Eastern modes.  The piano gradually builds momentum, returning to the mood of the opening and leading back finally to a varied and rousing restatement of the opening theme of the first movement of the Concerto. The piano gradually builds momentum, returning to the mood of the opening and leading back finally to a varied and rousing restatement of the opening theme of the first movement of the Concerto.  | ||||||||||

From The Fair at Sorochinsky Introduction – “A Hot Summer Day in Little Russia” Modest Musorgsky, one of the mavericks of nineteenth-century Russian music, left very few completed scores by the time of his early death from alcoholism. Of his meager output, the opera Boris Godunov, some of his songs, the short orchestral score St. John's Eve on Bare Mountain and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition, were completed at his death and have stood the test of time, being now are considered among the greatest masterpieces of Russian music. Musorgsky was a proponent of Russian nationalism, and he was a member of the “Mighty Five,” together with Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, Cesar Cui and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, whose goal was to further the pan-Slavic movement and Russian nationalist music. At his death, Musorgsky left two operas unfinished and unorchestrated: Khovanshchina, a bloody story of intrigue surrounding the ascension to the throne of Peter the Great, and the comic opera The Fair at Sorochinsky, based on a short story by Nikolay Gogol about a love affair at a country fair. Musorgsky incorporated his tone poem St. John’s Eve on Bare Mountain as a dream sequence of a peasant lad in the opera (As he did with so much of Musorgsky’s music, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov recomposed it as the familiar and much altered A Night on Bald Mountain.) There have been numerous attempts to complete and orchestrate The Fair at Sorochinsky, none of them fully satisfactory, but the 1930 version by Vissarion Shebalin (1902-1963) is the most accepted one. The opening Introduction  and the closing Gopak dance are the two best-known excerpts. and the closing Gopak dance are the two best-known excerpts. | ||||||||||

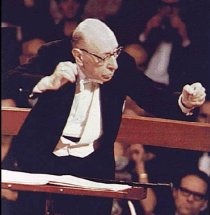

Suite from The Firebird “He is a man on the eve of fame,” said Sergey Diaghilev, impresario of the famed Ballets Russes in Paris, during the rehearsals for Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird. In 1909 Stravinsky, viewed as a budding composer just coming out from under the tutelage of Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, got what can be called his big break, thanks to the laziness of the composer Anatoly Lyadov. Early in the year Diaghilev had written Lyadov: “I am sending you a proposal. I need a ballet and a Russian one, since there is no such thing. There is Russian opera, Russian dance, Russian rhythm – but no Russian ballet. And that is precisely what I need to perform in May of the coming year in the Paris Grand Opera and in the huge Royal Drury Lane Theater in London…The libretto is ready…It was dreamed up by us all collectively. It is The Firebird – a ballet in one act and perhaps two scenes.” When Diaghilev heard that after three months Lyadov had only progressed so far as to buy the lined paper, he withdrew the commission and offered it to Aleksander Glazunov and Nikolay Tcherepnin, who both turned him down. In desperation he turned to the unknown Stravinsky. Stravinsky finished the score in May 1910, in time for the premiere on June 25. It was an instant success and has remained Stravinsky's most frequently performed work. Its romantic tone, lush orchestral colors, imaginative use of instruments and exciting rhythms outdid even Stravinsky’s teacher, Rimsky-Korsakov, the Russian master of orchestration. It required an immense orchestra and the first suite Stravinsky extracted from the ballet in 1911 strained symphony orchestras’ resources. In order to make it more accessible, he assembled in 1919 a suite for the concert hall, modifying the orchestration to conform to the resources of a modest orchestra. He re-orchestrated the suite in 1945, adding some of the music omitted from the original ballet while retaining the reduced orchestration. The ballet, taking its plot from bits of numerous Russian folk tales, tells the story of the heroic prince, the Tsarevich Ivan who, while wandering in an enchanted forest,  encounters the magic firebird as it picks golden fruit from a silver tree. encounters the magic firebird as it picks golden fruit from a silver tree.  He traps the bird but, as a token of goodwill, frees it. As a reward, the bird gives Ivan a flaming magic feather. At dawn Ivan finds himself in a park near the castle of the evil magician Kashchey. Thirteen beautiful maidens, captives of Kashchey, come out of the castle to play in the garden He traps the bird but, as a token of goodwill, frees it. As a reward, the bird gives Ivan a flaming magic feather. At dawn Ivan finds himself in a park near the castle of the evil magician Kashchey. Thirteen beautiful maidens, captives of Kashchey, come out of the castle to play in the garden  but one of them in particular, the beautiful Tsarevna, captures Ivan’s heart. but one of them in particular, the beautiful Tsarevna, captures Ivan’s heart.  As the sun rises, the maidens have to return to their prison and the Tsarevna warns Ivan not to come near the castle lest he fall under the magician’s spell as well. In spite of the warning, Ivan follows and opens the gate of the castle. With a huge crash Kashchey and his retinue of monsters erupts from the castle in a wild dance, whose drive and clashing harmonies foreshadow The Rite of Spring. As the sun rises, the maidens have to return to their prison and the Tsarevna warns Ivan not to come near the castle lest he fall under the magician’s spell as well. In spite of the warning, Ivan follows and opens the gate of the castle. With a huge crash Kashchey and his retinue of monsters erupts from the castle in a wild dance, whose drive and clashing harmonies foreshadow The Rite of Spring.  With the help of the magic feather Ivan calls the Firebird who overcomes Kashchey and tames the monsters by lulling them to sleep. With the help of the magic feather Ivan calls the Firebird who overcomes Kashchey and tames the monsters by lulling them to sleep.  In the end the captives are freed from the spell and Tsarevich Ivan and the Tsarevna are married in a grand ceremony culminating in an apotheosis of the Firebird. In the end the captives are freed from the spell and Tsarevich Ivan and the Tsarevna are married in a grand ceremony culminating in an apotheosis of the Firebird.  | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2018 | ||||||||||