| Wagner & Rimsky-Korsakov and Brahms Double Concerto | ||||||||||

Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102 It does not pay to get involved in other people’s' marital squabbles. When Brahms's friends of 30 years, the violinist Joseph Joachim and his wife entered into a messy divorce battle, Joachim accused Brahms of taking his wife's side and broke off all contact with his friend. The concerto was Brahms's peace offering; and while it brought the two friends back together, they never resumed the warmth of their original friendship. By adding the cello, Brahms also partially fulfilled a promise to Robert Hausmann, cellist of the Joachim quartet, to write a cello concerto. The material for the concerto, composed during the summer of 1887, originated as sketches for a fifth symphony that never materialized. But Brahms continued to revise it even after the premiere, which took place in October 1887 with Joachim and Hausmann as soloists. By the date of the Double Concerto, Brahms considered himself an “elder statesman” of music, looking to the past rather than to the future. The Concerto has little of the virtuosic glitter of most Romantic concertos, composed by and for musicians with competitive technical showmanship. Rather, it is introspective and subdued. There are no technical acrobatics for either of the two soloists, only the intensity of the themes and their development drive the work. Most double concertos feature identical instruments or at least instruments of similar range in order to insure equality when both soloists are in "opposition" or perfect blending when they are in "accord." The combination of extremes in this concerto had only some distant precedents in double concertos and symphonies concertantes for violin and cello by Vivaldi, Telemann, J.C. Bach, Carl Stamitz and Louis Spohr. Listeners used to pyrotechnic fiddling will find none of that in this Concerto. Surprisingly, the cello is the dominant instrument of the two soloists, creating a somber, autumnal cast to the entire work. The presentation of the themes throughout this concerto comes in stages, so that a complete melody emerges often after a considerable length of time. A case in point is the opening of the Concerto, which introduces a motivic unit within the main theme, interrupted by a long cadenza for the cello.  The orchestra then presents the beginning of the second theme, The orchestra then presents the beginning of the second theme,  after which both soloists engage in another cadenza – the last either soloist will see in this piece. The complete first theme occurs only several minutes into the movement. after which both soloists engage in another cadenza – the last either soloist will see in this piece. The complete first theme occurs only several minutes into the movement.  A mini-development of motivic material from the first theme delays the introduction of the third and final theme for this long movement. A mini-development of motivic material from the first theme delays the introduction of the third and final theme for this long movement.  After that, the movement becomes a rhapsodic interplay between the soloists and the orchestra in which the three themes are dissected and reconstituted in a myriad of ways, straying into distant keys and exploring the limits of the possible sonorities of the instruments. Formally, the movement strays considerably from the sonata form model. After that, the movement becomes a rhapsodic interplay between the soloists and the orchestra in which the three themes are dissected and reconstituted in a myriad of ways, straying into distant keys and exploring the limits of the possible sonorities of the instruments. Formally, the movement strays considerably from the sonata form model. The Andante is a simple ABA form. The two soloists have nothing more that long singing lines that interweave around each other – in a similar manner to the second movement of Bach's Concerto in d minor for two violins and Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola. It opens with a four-note motive in the winds. These four notes form the beginning of the main theme of the movement, introduced by the violin and cello playing an octave apart.  There is only one new theme, in the B section. There is only one new theme, in the B section.  In the Finale, Brahms roles out an astonishing number of themes, only some of them separated by the rondo.  The clue to rationale for the melodic proliferation in this movement rests with its relationship to the dances of the time. Waltzes and polkas introduce one melody after another, only periodically punctuated by a refrain. Popular – and inauthentic – Gypsy music followed the same pattern, and the rondo theme recalls Brahms Gypsy and Hungarian dances. One of the subsidiary themes harks back to the theme of the Andante, opining with the same four notes. The clue to rationale for the melodic proliferation in this movement rests with its relationship to the dances of the time. Waltzes and polkas introduce one melody after another, only periodically punctuated by a refrain. Popular – and inauthentic – Gypsy music followed the same pattern, and the rondo theme recalls Brahms Gypsy and Hungarian dances. One of the subsidiary themes harks back to the theme of the Andante, opining with the same four notes.  Ralph Vaughan Williams once recalled hearing the Concerto played as a piano trio in Berlin in 1897 with Joachim and Hausmann as soloists and Karl Barth as the pianist taking the place of the orchestra. We tend to forget how difficult it was to disseminate orchestral music before the days of sound recording. In those days piano and chamber transcriptions were the most popular way to familiarize the public at large with new orchestral compositions and were a thriving industry. Brahms himself may have transcribed the Concerto. | ||||||||||

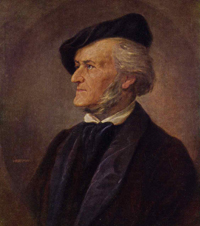

Overture to The Flying Dutchman In 1840 Richard Wagner left his post at the Opera of Riga and headed to Paris to seek his fortune. Crossing the North Sea his ship was caught in a violent storm that reminded him of a picturesque Nordic legend in poet Heinrich Heine’s Memorien. It is the tale of a Dutch sailor who tried to round the Cape of Good Hope in a gale, swearing in his rage that he would fight against Hell itself to reach his destination. For this blasphemy he is condemned to fight continual storms, making landfall only once every seven years until the end of time unless released from the curse by the love of a faithful woman. He is finally rescued from this ordeal by Senta, who is unfortunately already betrothed to someone else. The complications end in the death and apotheosis of the lovers. One of Wagner’s early music dramas – he refused to call them operas – The Flying Dutchman inaugurated the string of nine music dramas based on medieval legends or themes. It also introduces the motif of redemption through love that pervades the composer’s entire oeuvre. The overture comprises all the important themes from the opera: the harmonically hollow horn and bassoon theme of the tortured Dutchman accompanied by the howling winds and undulating waves;  the refrain for English horn from the ballad of the Dutchman that has captured Senta’s imagination and becomes identified with her love for him; the refrain for English horn from the ballad of the Dutchman that has captured Senta’s imagination and becomes identified with her love for him;  a rousing chorus of the village sailors, which contrasts with the sound of the Dutchman's ghostly crew. a rousing chorus of the village sailors, which contrasts with the sound of the Dutchman's ghostly crew.  In his early music dramas, The Flying Dutchman, Lohengrin and Tannhäuser, Wagner began to develop a system of melodic motives, or Leitmotiven, to musically represent people, events and even abstract ideas. The culmination of his work occurs in the tetraolgy, The Ring of the Nibelungen, which contains nearly 100 such themes. | ||||||||||

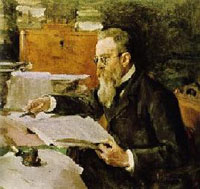

Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36 In the development of the tradition of Russian national music, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov fills a place of honor. Musically self-taught, he trained originally as a naval officer and served in that capacity from 1862 to 1873. Throughout his naval career he studied music on the side until 1871 when he won a faculty position at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in spite of the fact that he had little formal training. Henceforth, he taught and encouraged nearly every young Russian composer from Alexander Glazunov and Anton Arensky to Igor Stravinsky and Sergey Prokofiev. After the deaths of Alexander Borodin and Modest Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov edited and completed their manuscripts – especially their operas – and had them published. The fact that his “corrected” versions of Mussorgsky’s works used to dominate the original versions on stage and in recordings attests to the sheer force of his influence. He also helped publish the works of many other Russian composers. Rimsky-Korsakov composed the Russian Easter Festival Overture in 1888 and conducted the premiere the same year. He took his themes from the Obikhod, a famous collection of canticles of the Russian Orthodox Church, and actually called it Svetliy prazdnik (“Bright Holiday”), the traditional Russian name for Easter. The work reflects his fascination with the legends and rituals of pagan and early Christian Russia. He prefaced the score with quotes from the 68th Psalm and the 16th chapter of Mark, adding some words of his own that allude to a more primitive vernal symbolism, in keeping with his own pantheistic outlook. In order to perfectly appreciate the Overture, Rimsky-Korsakov believed that one should have attended at least one Easter morning service in a Russian Orthodox Church. In his autobiography, he wrote some comprehensive program notes for the work: “This legendary and heathen side of the holiday, this transition from the gloomy and mysterious evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious merry-making of Easter Sunday, is what I was eager to reproduce in my overture…” A lengthy slow introduction is based on the melody “Let God arise,”  alternating with the ecclesiastical melody “An angel cried out” for solo cello. alternating with the ecclesiastical melody “An angel cried out” for solo cello.  The beginning of the Allegro is based on the chant “Let them also that hate Him flee before Him,” The beginning of the Allegro is based on the chant “Let them also that hate Him flee before Him,”  which introduces the holiday mood of the Russian Orthodox service with a reproduction of the joyous, almost dancelike tolling of bells. which introduces the holiday mood of the Russian Orthodox service with a reproduction of the joyous, almost dancelike tolling of bells.  The Obikhod theme, “Christ is arisen,” forms a subsidiary part of the overture, appearing amid the trumpet blasts and the tolling of the bells, constituting a triumphant coda. The Obikhod theme, “Christ is arisen,” forms a subsidiary part of the overture, appearing amid the trumpet blasts and the tolling of the bells, constituting a triumphant coda.  | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2019 | ||||||||||