| Grieg & Vaughan Williams and Elgar's Enigma Variations | ||||||||||

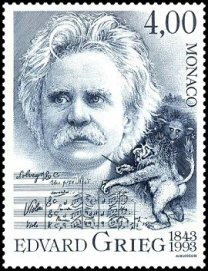

From Holberg's Time (Holberg Suite), Op. 40 The most successful and best-known of nineteenth century Scandinavian composers, Edvard Grieg was one of the great exponents of Romantic nationalism. He saw it as his role in life to bring Scandinavian musical and literary culture to the attention of the rest of Europe, and he succeeded in this endeavor. He was most comfortable with and excelled in the smaller musical forms, such as intimate songs and short piano pieces. As composer, pianist and conductor, he became a sought-after fixture in Europe’s music centers. His wife Nina was an accomplished singer, and the two traveled extensively together, popularizing his songs and piano works. In the process he helped bring the writings of Scandinavian poets – the best known being the playwright Henrik Ibsen– to the attention of the rest of Europe. As an student he had been a failure. He quit school at 15 never to return. Under the sponsorship of Norwegian violinist Ole Bull he was granted a scholarship to the Conservatory in Leipzig but hated his teachers there and never forgave them their conservatism and pedantry. Understandably, he was not too happy with the constraints of the classical sonata type, and of all his surviving output only eight works fall into this category: a youthful symphony, the famous piano concerto, a string quartet, a piano sonata, the three violin sonatas and the cello sonata. In all his other compositions he insisted on the freedom of form so dear to the Romantic tradition. Grieg composed the Suite From Holberg’s Time in 1884 to commemorate the bicentennial of the birth of the Norwegian dramatist Ludvig Holberg. Originally written for the piano, he orchestrated the Suite a year later. In the Suite Grieg tried to recreate past musical styles, especially the suites of the French Baroque keyboard masters, Jean-Philippe Rameau and François Couperin, who were Holberg’s contemporaries. The Suite comprises four Baroque dances of French origin preceded by a Prelude. However, the style of Domenico Scarlatti and J. S. Bach, born a year after Holberg, can be heard respectively in the toccata-like figuration of the Prelude  and the ornamental melody in the Air. and the ornamental melody in the Air.  Listeners of a certain age may recall the Sarabande as the theme music from the television show of the 50s I Remember Mama, about the life of a Norwegian immigrant family in San Francisco. Listeners of a certain age may recall the Sarabande as the theme music from the television show of the 50s I Remember Mama, about the life of a Norwegian immigrant family in San Francisco.  The Gavotte is probably the most French-sounding of the movements The Gavotte is probably the most French-sounding of the movements  and the Rigaudon provides a sprightly, although rather inconsequential conclusion. and the Rigaudon provides a sprightly, although rather inconsequential conclusion.  Throughout the Suite, one never quite loses sight of the fact that it is the work of a nineteenth century composer. Throughout the Suite, one never quite loses sight of the fact that it is the work of a nineteenth century composer. | ||||||||||

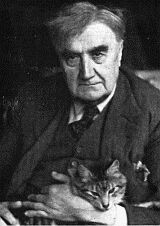

Concerto for Oboe and String Orchestra Ralph Vaughan Williams came from a distinguished family: his paternal grandfather was the first Judge of Common Pleas; his maternal grandparents were Josiah Wedgwood III and one of Charles Darwin sisters. Although the family encouraged his youthful musical talents, they later disapproved of his choice of music as a career; he prevailed, graduating with a Mus.B from Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1894. His progress was slow and uncertain. He went to Berlin in 1897 to study with Max Bruch, and to Paris in 1908 to take lessons from Maurice Ravel. But he was drawn to Elizabethan and Jacobean music. His music became rooted in Tudor polyphony, uncovering that rich heritage for modern audiences. He also had a passion for English folk music; his collection of over 800 folksongs, on which he worked between 1903 and 1910, and his selection of the songs for The English Hymnal in 1906 helped set the stage for the future development of his musical language. Considered radical in his young days and a lifelong agnostic (despite his contributions to religious music), he believed that music was the birthright of every individual. In his long, productive life – his last symphony was premiered just four months before his death at age 85 – Vaughan Williams practiced what he preached. He wrote music for numerous instrumental and vocal combinations, as well as for levels of sophistication and performing ability. Inspired by the virtuosity of the famed English oboist, Léon Goossens, Vaughan Williams composed this concerto in 1944. It is a deliberately small-scale work, more noted for its craftsmanship than for its meaning, message or inspiration. Vaughan Williams agreed with the conductor Sir Henry Wood that it would be unsuitable for the Promenade Concerts performed in cavernous Albert Hall but would need a more intimate setting to be effective. The lighthearted atmosphere of the concerto can be seen already in the titles for the three movements: Rondo Pastorale, Minuet & Musette, Scherzo Finale. The solo oboe in the symphony orchestra is often the voice for lyrical or deeply emotive moments. In this concerto, it assumes one more role - acrobatic agility in the finale. It thus requires a master of the instrument to make the solo part sound effortless rather than awkward. The Concerto opens with an introductory sinuous solo melisma that recalls the composer’s The Lark Ascending and, for those that are familiar with the earlier work, inevitably evokes a comparison between the emotive qualities of oboe and violin.  Typically, Vaughan Williams’ indulges his penchant for weaving English folksong into his music. Aptly titled “Pastorale,” the first movement presents a stream of folk-like melodies. This familiar idiom is characterized by its own particular mode, not quite minor and often sounding pentatonic because the melodies concentrate on five notes of the mode. The Allegro takes up a more energetic tune with a staccato theme with a toggling motive. Typically, Vaughan Williams’ indulges his penchant for weaving English folksong into his music. Aptly titled “Pastorale,” the first movement presents a stream of folk-like melodies. This familiar idiom is characterized by its own particular mode, not quite minor and often sounding pentatonic because the melodies concentrate on five notes of the mode. The Allegro takes up a more energetic tune with a staccato theme with a toggling motive.  In the middle section, the tempo slows to that of the introduction, In the middle section, the tempo slows to that of the introduction,  and the oboe engages in an elaborate accompanied cadenza, complete with “bird-call” trills. and the oboe engages in an elaborate accompanied cadenza, complete with “bird-call” trills.  In a sense, the pastoral progresses through a full day from dawn and sundown, birdcall serenades flanking a shepherd’s workday. In a sense, the pastoral progresses through a full day from dawn and sundown, birdcall serenades flanking a shepherd’s workday.Since the soloist is seldom silent, Vaughan Williams tones down the virtuosic passagework in the short Minuet and Musette. Seldom repeating large sections of music, the Minuet does not conform to the standard repeat structure of the eighteenth-century model.  The Trio, however, is in a slower tempo The Trio, however, is in a slower tempo  and is followed by a partial repeat of the Minuet. and is followed by a partial repeat of the Minuet.The Finale is a technical showpiece and extremely difficult to play. A series of rapid, wide leaps opens the movement, a motivic gesture rather than a true theme.  As in the first movement, Vaughan Williams periodically varies the tempo spinning out one melody after another, allowing the instrument to display its lyrical voice. As in the first movement, Vaughan Williams periodically varies the tempo spinning out one melody after another, allowing the instrument to display its lyrical voice.  And, of course, there are the British folk melodies. And, of course, there are the British folk melodies.  | ||||||||||

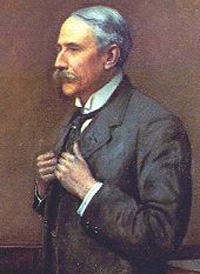

Enigma Variations, Op.36 If you look at photographs of Edward Elgar, read about his tastes or listen to his music, he appears to project the stereotype of Imperial Britain’s aristocracy or, as composer Constant Lambert described Elgar, “[the image of]... an almost intolerable air of smugness, self-assurance and autocratic benevolence...” His military bearing, walrus moustache, country gentleman’s dress – all very proper and Edwardian – matched his conservative, violently anti-Liberal ideas. His style appeared to have been fostered and fully sanctioned by the equally conservative Royal College of Music. The reality was very different: Elgar was born to a lower middle class family and never served in the army. Worst of all, his father was a music store owner, or as the British used to say, “in trade.” And he was a Catholic, which did not help either. He was nervous, insecure, and prone to depression and hypochondria; he always carried a chip on his shoulder for not being “fully accepted.” Musically, he was completely self-taught. But to the chagrin of Britain’s music establishment, Elgar – an “outsider” – was the first English composer since Henry Purcell (1659-1695) to achieve world fame. It was the Enigma Variations, composed in 1899 when he was 42, that propelled him out of his parochial obscurity to worldwide recognition. Elgar had begun the Variations as a private amusement for his wife, Alice, whom he adored. He created musical portraits of their friends, later turning them into a proper orchestral composition at her suggestion. The expressive and stately theme was his own, but Elgar claimed that he had employed a second, hidden theme combined with the main theme. This second theme has remained a mystery to this day, although in later years Elgar said that it was derived from a melody “...so well-known that it is strange no one has discovered it.” The Elgar friends and their peculiarities are portrayed in the 14 variations, each of which is headed by a nickname or initials, making some of the identities a puzzle as well – although by now scholars have figured them out. The theme: | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2019 | ||||||||||