| VIVA ITALIANO! | ||||||||||

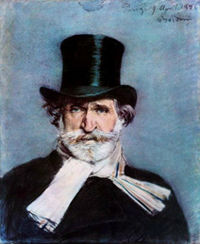

From Nabucco Overture Chorus, Va, pensiero sull’ali dorate Giuseppe Verdi achieved astounding success as a musical dramatist with his ability to capture in music the psychological depth of his characters. He was the king of Italian opera through much of the nineteenth century and premiered works in all the major cities of Italy, as well as in Paris, St. Petersburg and Cairo. So in demand was he that he referred to the long period in which he produced a constant stream of operas as his years as a galley slave. He composed his first great success, Nabucco, as he mourned the untimely death of his first wife and two young children, and he expressed all his poignant longings in the chorus, Va, pensiero, of the exiled Israelites. Born of stolid peasant and rural tradesman stock, Verdi was always unconventional without being openly rebellious. Although some of his most emotionally charged music involves religious characters and scenes, not to mention his great Requiem, he was not religious himself. After the death of his first wife, he lived for many years out of wedlock with the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, marrying her only later in life. His sympathy for this unconventional lifestyle is reflected in his portrayal of Violetta and Alfredo’s relationship in La traviata. Verdi’s streak of independence and attraction to politically compromising plots was often blocked by the Italian censors who passed on all stage representations. Un ballo in maschera, originally written about a true incident in the life of the playboy King Gustav III of Sweden, had to be reset in Boston about a fictitious colonial governor; and Rigoletto, based on a play by the French playwright Victor Hugo about King François I, had to be reset in Mantua about a fictitious duke. Verdi was a staunch supporter of a united Italy. In 1861 as Garibaldi’s militias stormed their way north through the peninsula, “Viva Verdi (Vittorio Emmanuele Re d’Italia),” became a rallying cry for the patriots in support of the king of the new nation. Verdi himself served as a deputy in the country’s first parliament but found active politics disillusioning. Nevertheless, his operas are full of his social and political idealism, sometimes hidden, at others flamboyantly overt as in his brutal attacks on the Church and religious intolerance in Don Carlos. Personally, he liked nothing better than a life of quiet intimacy with Giuseppina and a group of close friends and associates in his beautiful rural villa at Sant’Agata in the Parma region of Italy. In Nabucco, we get a glimpse of the composer at the unpromising beginning of his career. The year was 1842. His first two operas had been dismal failures and he had vowed never to write another note. The impresario Bartolomeo Merelli, however, presented the young Verdi with the libretto for Nabucco, which the composer patently ignored. When he casually looked through it five months later, he was hooked. The plot of Nabucco, from the Book of Daniel – with significant non-biblical accretions – concerns the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. by King Nebuchadnezzar (Nabucco), his Divine punishment of madness and repentance. Verdi encapsulates the essentials of the plot characterizing both the oppression of the Babylonians  with the homesick lament of the enslaved Hebrews from Act III, “Va, pensiero sull’ali dorate” (Fly, thoughts, on golden wings). This chorus not only became an instant sensation, but also became the “theme song” for the Risorgimento (the uprising for the unification of Italy). with the homesick lament of the enslaved Hebrews from Act III, “Va, pensiero sull’ali dorate” (Fly, thoughts, on golden wings). This chorus not only became an instant sensation, but also became the “theme song” for the Risorgimento (the uprising for the unification of Italy).  | ||||||||||

| Giuseppe Verdi Anvil Chorus from Il trovatore Il trovatore has one of opera’s most ridiculous and convoluted plots, based on El trobador, a Spanish melodrama by Antonio Garcia Gutierrez (1813-1844). The Count di Luna’s brother is believed to have perished at the hands of a Gypsy, whose daughter Azucena saved him and brought him up as her own son, Manrico. Now an adult, Manrico has distinguished himself as a warrior and troubadour and finds himself di Luna’s rival for the love of Leonora, who loves Manrico. By the time it’s all over, Leonora has swallowed poison rather than submit to di Luna, who has executed Manrico, only to find out from Azucena that he has killed his own brother. “Vedi! Le fosche notturne spoglie” (See! The somber hues of night), the so-called Anvil Chorus, is sung by a band of Gypsies as Count di Luna prepares to besiege the castle where Manrico is harboring Leonora. Its name derives from the accompaniment of actual anvils in the percussion section of the orchestra.  The best-known passage from the scene is the choral refrain, to anvil accompaniment. The best-known passage from the scene is the choral refrain, to anvil accompaniment.  | ||||||||||

Overture to La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie) One of the most prolific opera composers of all time, Gioacchino Rossini wrote nearly 40 operas by the time he was 37 – then quit. For the rest of his long life he composed only sporadically and, except for church music, mostly small works he tossed off for the entertainment of his friends (He published over 150 of them in a collection which he called Péchés de vieillesse – Sins of Old Age). La gazza ladra was Rossini’s first great success (following two dismal failures) in that bastion of Italian opera, Milan’s La Scala Opera House. The premiere in May of 1817 was described by Stendhal, a musicologist and music historian as well as a great novelist, as the most successful he had ever attended. Starting with the opening drum rolls – two of the main characters in the libretto are returning soldiers – the Overture has a considerably closer connection with the rest of the opera than is customary with Rossini (The overture to The Barber of Seville did duty, essentially unchanged, twice before as overtures to earlier tragedies!) The plot of the opera concerns Ninetta, a servant girl sentenced to death on suspicion of stealing a silver spoon. After considerable confusion, she is saved from the gallows when the spoon is found in a magpie nest. Rossini had his own “system” for overture writing: never before the evening of the first performance. In his memoirs he recalls, “I wrote the overture to La gazza ladra on the actual day of the first performance of the opera, under the guard of four stage-hands who had orders to throw my manuscript out of the window, page by page, as I wrote it, to the waiting copyist – and if I didn’t supply the manuscript, they were to throw me out myself. Nothing excites inspiration like necessity; the presence of an anxious copyist and a despairing manager tearing out handfuls of his hair is a great help. In Italy in my day all managers were bald at thirty.” Rossini was hard on orchestra players, especially the woodwinds, but in this Overture, he features the percussion. The opening snare-drum solo, as well as the use of triangle, four timpani and bass drum throughout, suggest Ottoman Janissary music, but nobody specifies from which war the soldiers in the plot are returning.  However rushed or recycled, Rossini’s overtures always contain a bouquet of memorable tunes, to the point where even professionals tend to forget which overture they belong to. For La gazza ladra, after the snare drum riff, Rossini spins out a little Italian tarantella, However rushed or recycled, Rossini’s overtures always contain a bouquet of memorable tunes, to the point where even professionals tend to forget which overture they belong to. For La gazza ladra, after the snare drum riff, Rossini spins out a little Italian tarantella,  what was to become a proverbial oboe riff what was to become a proverbial oboe riff  and the inauguration of the “Rossini rocket.” This last device, the repetition of a melody, each time louder, faster and more fully orchestrated became one of the composer’s standard effects. Here is the beginning – with snare drum again – and the climax. and the inauguration of the “Rossini rocket.” This last device, the repetition of a melody, each time louder, faster and more fully orchestrated became one of the composer’s standard effects. Here is the beginning – with snare drum again – and the climax.  & &  | ||||||||||

| Giuseppe Verdi Triumphal March and Finale from Aïda Aïda, premiered in 1871, involves a classic love triangle. Radames, leader of the Egyptian army, loves Aïda, a captures Ethiopian princess, now a slave to the Egyptian princess Amneris, who also loves Radames. During the great procession celebrating another victory over the Ethiopians, Aïda discovers her father Amonasro in disguise among the captives. He urges her to seduce Radames into deserting over to the Ethiopians, but the plot is discovered by Amneris and the High Priest Ramfis. Radames is put on trial but refuses to defend himself and is condemned to be buried alive. While Amneris prays over his tomb, Radames discovers Aïda hidden in a corner, and the lovers consume the remaining oxygen in a final farewell duet. Despite the fact that the scenario had been provided by one of the most noted Egyptologists of the period, it abounds in anachronisms and historical mistakes. The site of Radames’s consecration, for example, was set in the Temple of Vulcan, a Roman god who was never worshipped by the Egyptians and who made his appearance under the Romans around 700 years after the timeframe of Aïda. Probably one of the most popular scenes in the entire operatic literature, the so-called “Triumphal Scene” from Act II, Scene 2, displays the full range of Verdi’s powers: procession, choruses, ballet and a finale in which all the characters simultaneously pour out their deepest emotions. Preceded by a grand trumpet fanfare,  in the opera, the chorus opens the celebration. in the opera, the chorus opens the celebration.  The March accompanies the victorious Egyptian army, led by Radames, as it approaches the King’s throne, The March accompanies the victorious Egyptian army, led by Radames, as it approaches the King’s throne,  followed by the priests followed by the priests  and finally the captive Ethiopians. and finally the captive Ethiopians. At the Finale, as the lovers die in the underground chamber, Amneris and the priests pray to the goddess Isis and the god Ftha. | ||||||||||

Pini di Roma (Pines of Rome) Ottorino Respighi was one of the most imaginative orchestrators of the first part of the twentieth century. While most of his musical studies were undertaken in Italy, he spent two crucial years in Russia where he took lessons in orchestration from Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. Respighi developed a masterful technique in the use of instrumental colors and sonorities. Firmly rooted in the late-Romantic tradition, he maintained this style with only marginal influence from the revolutionary changes in music that occurred during his lifetime. Respighi was a musical nationalist, keenly interested in reviving Italy’s musical heritage, especially its instrumental music. Beginning in 1906 he undertook to transcribe and arrange music from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, editing the works of Claudio Monteverdi and Tomaso Antonio Vitali. In 1917 he published the first of his three suites of Ancient Airs and Dances, based on Italian and French lute music, mostly from the early seventeenth century. In 1927 he composed Gli uccelli (The Birds), a five-movement suite using eighteenth-century keyboard works imitating birdsongs. Indeed, most of his works are based on the music of the past. Composed in 1924, Pini di Roma is the second in Respighi's trilogy of tone poems inspired by different aspects of the city of Rome and its history. The score, describing four widely separated locations in the city, contains a detailed description of this programmatic music: The Pines of the Villa Borghese (a country estate with enormous grounds belonging to one of Rome’s most notable Renaissance families):Ironically, while Respighi uses the giant pines as symbols of Rome’s ancient past, these trees are relative newcomers to the eternal city. The species was introduced from Sardinia, probably in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. There has been some controversy regarding Respighi’s political affiliation. The fact that Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was particularly fond of the composer’s “Roman” tone poems and that Respighi accepted various honors from the Fascist government has led to the conclusion that Respighi was a Fascist supporter himself. His supporters, however, cite the composer’s intervention in 1931 to save Arturo Toscanini from a Fascist mob in Bologna, and his remarks against the regime for threatening the conductor. There is also an allegedly hidden anti-Fascist message in the final scene of his opera Lucrezia, written in 1935-6, when Fascism was at its height: "Death to the tyrants, you be leader, Brutus! - Freedom, to Rome!" | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2018 | ||||||||||