| TCHAIKOVSKY SYMPHONY No. 6 | ||||||||||

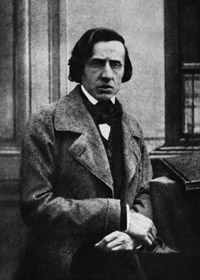

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 The son of a French father and Polish mother, Frédéric Chopin was born and grew up in Poland; but after the collapse of the Polish revolution against Russia in 1831, he went into exile to France. He settled in Paris, which was then the center of Polish émigrés. Because of his own financial success, he was able to play at charity concerts held for his poorer exiled compatriots and organize similar events. Although he was never able to return to his native country, his solo piano works include numerous polonaises and mazurkas that bear witness to his regard for his native land. In accordance with his will his sister brought his heart, preserved in Cognac, to Warsaw where it was placed in an urn installed in a pillar of the Church of the Holy Cross in Krakowskie Przedmiescie. Chopin’s chosen medium was the piano as a solo instrument. In his late teens he did try to unite the piano with the orchestra, creating, in addition to the two piano concertos, the Variations Op.2, Fantasia on Polish Airs Op. 13, the Concert Rondo Op. 14 and the Grande Polonaise Op. 22. Admittedly uncomfortable with the orchestral medium, after age 20 he never again wrote for orchestra. In all these works, the orchestral scoring is so light that in the nineteenth century it was fashionable to reorchestrate and “improve” the accompaniment. It is probable, however, that Chopin intended the orchestra to serve merely as a background fabric for the soloist. He himself was known to have had a rather light touch at the piano, and heavy orchestral accompaniment would have drowned him out. The concentration on solo piano works, however, could not have brought in enough income to sustain him; most of his life was devoted to teaching piano, in which he was a master. The e minor Concerto, although numbered No.1, was composed later than the second (1830) but was published first. It was premiered in October 1830 in Warsaw, with the composer at the piano. He wrote to a friend the next day: “I was not a bit, not a bit nervous and played the way I play when I am alone, and it went well...” This is a pianist’s concerto with all the frills and furbelows for the soloist, but it also contains the kind of poignantly lyric melodies that were to characterize the composer’s subsequent music for solo piano. The opening movement, Allegro maestoso, is in the classical tradition, with a long orchestral introduction in which Chopin presents all the main themes of the movement.  & &  & &  When the piano enters, it is with embellishements of these themes. The development too, is in the traditional classical form. When the piano enters, it is with embellishements of these themes. The development too, is in the traditional classical form. The composer wrote about the second movement, Romance: Larghetto: [it is] “of a romantic, calm and rather melancholy character...a kind of reverie in the moonlight on a beautiful spring evening.” A short orchestral introduction precedes the entrance of the piano, which this time presents the principal theme of the movement.  The movement is a standard ABA form, as well as a set of free variations, or fantasy, for the pianist. The middle section presents a contrasting theme in a contrasting mood. The movement is a standard ABA form, as well as a set of free variations, or fantasy, for the pianist. The middle section presents a contrasting theme in a contrasting mood.  The form, however, is less important than the unusual modulations and the pianistic decorations. To balance the introduction, Chopin also provides a substantial coda, yet one more fantasy on the theme. The form, however, is less important than the unusual modulations and the pianistic decorations. To balance the introduction, Chopin also provides a substantial coda, yet one more fantasy on the theme.The finale, Rondo, vivace, is rhythmically related to the Krakoviak, a rapid dance originating around the city of Krakow and considered Poland’s national dance. The opening piano refrain reappears a number of times,  separated by graceful, highly ornamented or dancelike melodies. separated by graceful, highly ornamented or dancelike melodies.  & &  | ||||||||||

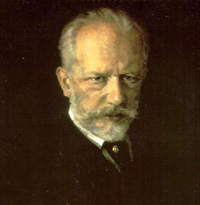

Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, Pathétique This Symphony was Tchaikovsky’s final completed work, premiered to a lukewarm reception on October 28, 1893 only nine days before the composer’s death from cholera. Although its emotional intensity and title, Pathétique, suggest that this was yet another manifestation of the composer’s periodic depression, or even a foreshadowing of his own death, the fact remains that Tchaikovsky was extremely pleased with this work from the moment he set to work on it. At the symphony’s second performance, as part of a memorial service for the composer, the audience seems to have suddenly perceived its significance, and it has remained a favorite ever since. Tchaikovsky’s original conception was that the symphony should have a program, much like Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, but he refused to specify what the program was, wanting the listener to guess it. His early, and by now well-known, scenario for the program reads: “The ultimate essence of the plan…is LIFE. First movement–all impulsive passion, confidence, thirst for activity. Must be short. (Finale DEATH – result of collapse). Second movement, love, third, disappointment, fourth ends dying away (also short).” The final version can be understood to conform to this program only in part, and then only in the first and fourth movements. That it bears little resemblance to the final version of the music is clear even at a first hearing. Still intending to call his work a “program” symphony, Tchaikovsky accepted his brother Modest’s suggestion of the Russian patetichesky, which the publisher insisted on translating into French, still the language of the Russian aristocracy and intelligentsia. The English reader, however, should be aware that the adjective pathétique actually means “highly emotional” and does not have the derogatory connotation of “pathetic.” The Symphony opens with a low bassoon solo introducing the first theme in a ponderous and pessimistic adagio.  The melody is then taken up in a nervous allegro and repeated by the successive sections of the orchestra. The melody is then taken up in a nervous allegro and repeated by the successive sections of the orchestra.  The emotional turmoil, however, is resolved in the second theme, among the most famous in the canon of memorable Tchaikovsky melodies. The emotional turmoil, however, is resolved in the second theme, among the most famous in the canon of memorable Tchaikovsky melodies.  The theme was specifically meant to be a transformation of Don José’s “flower aria” from Carmen – giving a hint as to the composer’s emotional take on love. The theme was specifically meant to be a transformation of Don José’s “flower aria” from Carmen – giving a hint as to the composer’s emotional take on love.  The second movement is a “waltz” in 5/4 time, giving the impression of alternating bars of 3/4 and 2/4.  Strangely enough, this meter works as a waltz, for despite its limping quality, one can imagine the alternating foreshortened 2/4 bars used for a lift or emotive pause, if the movement were actually to be used for dancing. It is a hybrid of a classical minuet and trio, or scherzo – with two themes and a series of repeats – and a ternary (ABA) song form customary for slow movements. The Trio (or B section), which proceeds with a constant timpani ostinato in the background, darkens the ballroom atmosphere. Strangely enough, this meter works as a waltz, for despite its limping quality, one can imagine the alternating foreshortened 2/4 bars used for a lift or emotive pause, if the movement were actually to be used for dancing. It is a hybrid of a classical minuet and trio, or scherzo – with two themes and a series of repeats – and a ternary (ABA) song form customary for slow movements. The Trio (or B section), which proceeds with a constant timpani ostinato in the background, darkens the ballroom atmosphere.  Like the first movement, the third is best known for its second theme, a sprightly march,  which follows a scurrying opening theme in rapid triplets, out of which one can already hear hints of the march theme. which follows a scurrying opening theme in rapid triplets, out of which one can already hear hints of the march theme.  As in the second movement, however, the composer utilizes an unusual metrical structure, creating an ambiguity between duple and triple time by composing the march in 12/8 time. The movement, in G major, seems almost to begin backwards with a series of themes in the relative e minor that gradually lead into the march theme in the principal key. As in the second movement, however, the composer utilizes an unusual metrical structure, creating an ambiguity between duple and triple time by composing the march in 12/8 time. The movement, in G major, seems almost to begin backwards with a series of themes in the relative e minor that gradually lead into the march theme in the principal key.The Finale can be interpreted as taking up the symphony’s original program. The opening theme, a series of short breathless, sighing motives, is a variation of the first theme of the opening movement and has the identical underlying harmony.  A programmatic interpretation of the movement suggests anxious struggle – in the rising sequences – and resignation upon the approach of the nothingness of death. It is particularly noteworthy in the history of symphonic finales in both its lugubrious tempo and fatalistic pessimism. A programmatic interpretation of the movement suggests anxious struggle – in the rising sequences – and resignation upon the approach of the nothingness of death. It is particularly noteworthy in the history of symphonic finales in both its lugubrious tempo and fatalistic pessimism. | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2018 | ||||||||||